Campus Wayfinding

“Wayfinding” is an age-old term that describes the various techniques used by travelers to find their way from place to place. Think of navigating by stars, or with a compass.

Wayfinding is also a concept that architectural firms and urban planners are increasingly taking into account as they design modern buildings. The reasons have not just to do with logistics, but with the safety and security of the people that use these buildings. Proper wayfinding can help individuals successfully navigate office buildings, hospitals, government centers and even entire towns and cities.

Modern wayfinding techniques, when applied to a college campus, offer the same logistical benefits plus a few added bonuses — including augmented security, according to Barbara Martin, CEO of KMA Design, in Canonsburg, Pa., and Mark VanderKlipp, president and principal at Corbin Design in Traverse City, Mich., a pair of wayfinding experts with experience on campuses around the nation.

Since founding KMA in 1996, Martin and her staff have coordinated well over 40 campus wayfinding projects at an array of schools, including the University of Pittsburgh, Stony Brook University, and Seton Hill University.

Modern wayfinding technologies include touch-screen kiosks, programmable LED signs and cell phone map applications. Many of these tools allow for greater interaction between security forces, campus residents and visitors.

Corbin Design has conducted more than 30 wayfinding projects on campuses like the University at Albany-State University of New York, Pennsylvania State University, and several other Big 10 schools. Drawing from experience, VanderKlipp says that modern wayfinding tools can augment existing campus safety systems and security forces during emergency circumstances. Net-worked interactive digital kiosks, for example, can be programmed to display information and announcements, including campus maps and emergency evacuation notifications. Students can also check their debit card balances.

“In regards to security, campus wayfinding focuses largely on helping people stay away from places that they shouldn’t be in, and letting visitors know building hours and rules,” says VanderKlipp. “Campus wayfinding typically supports security by communicating rules rather than reacting to emergency situations, though technology has evolved to support both objectives in new ways.”

KMA’s Barbara Martin says that many colleges are today adding LED electronic messaging boards, designed to convey emergency and non-emergency information to students and campus visitors.

“These signs are often tied into the police departments for [use] in the event of an emergency or evacuation,” Martin says. “Typically, the signs will be managed by the marketing department or similar agency, but the police or campus security will have an override system to control them during emergencies.”

Vandalism to these signs is an emerging threat to wayfinding that campus facilities managers frequently deal with. However, Martin says that new materials are being used in sign manufacturing, making it more difficult for vandals.

“For example, with an aluminum sign we might use a hard-finish paint, something similar to what’s used on a car,” she says. “Plus, we’ll add clear-coats on top of that, reducing the porosity and making it easier to wash off graffiti.”

The Science of Wayfinding

The Science of Wayfinding

“Two of the many things we have to consider when laying out a campus wayfinding plan are branding/marketing and the convenience for first-time visitors,” says Martin. “A big impression is made on a person within the first few seconds of them entering a campus in regards to whether or not they want to attend that school or whether they want their child to attend it.”

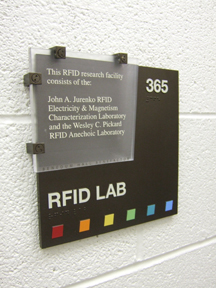

On top of labeling spaces and buildings, campus wayfinding provides interconnectivity between destinations, often taking visitors from large places to smaller and less obvious areas.

“For instance, campus signs will direct individuals to a general area where they are to have a meeting,” Martin says. “Once we get them to the building and the entrance, we provide them direction to their interior destination. That flow of signage has to go from one point to the next, then back out the building to where they parked.”

During the design stage of a project, wayfinding systems are often integrated with the college’s master plan and marketing objectives, ensuring that the scheme requires minimal updating in the decades after it is installed.

“We often begin campus wayfinding projects by conducting surveys,” Martin says. “We’ll survey staff, students, and visitors to find out some of their concerns with the campus and to determine problems that they have had in locating destinations. Based on their responses, we’ll develop an analysis that incorporates problem areas, places that lack signage, code violations, and other elements.”

From Charts to Apps

Smartphone applications that produce campus maps, and provide information about college historical sites and attractions, are some of the latest technologies in an ever-expanding arena of university wayfinding.

“The University of Texas at Austin utilizes an amazing iPhone app that provides a tremendous number of resources,” VanderKlipp says. “One of the best parts of the program is its mapping capability, which allows users to search for specific buildings on campus and make use of their Smartphone’s GPS capabilities to coordinate directions from place to place.”

Other schools are investigating the capabilities of the barcode application in physical spaces, VanderKlipp says. With barcode technology, campus visitors could photograph barcodes on informational signs using their phones and bring up websites with further background or history on the building or attraction.

VanderKlipp predicts that sometime in the not-too-distant-future, students, staff and visitors will hold their cell phone cameras up to a campus landscape and instantly receiving feedback on their phone’s screen about building names, where building entrances and offices are located, and other pertinent information.

Already such tools — known as “augmented reality applications” — are in use by the Metropolitan Transit Authority in New York City, and for commercial purposes, such as real estate listings.

“I think in the future, augmented reality locators will be an expectation that students, staff and alumni all have for their campuses,” VanderKlipp says.