Photo: The LPA study shows how much energy performance can be gained with smart, passive design strategies. | Photo Credit (all): LPA

A cost-benefit analysis examines a tiered approach to energy investments that can save schools significant money on annual operating expenses

By Kate Mraw

By Kate Mraw

The realities of funding school construction make it difficult for districts to weigh the short- and long-term benefits of moving their campuses to cleaner, healthier, more energy-efficient environments. Are energy-efficient strategies cost-prohibitive? The Sustainability & Applied Research team at LPA Design Studios recently worked with in-house designers and engineers, and partner Joeris General Contractors, to explore the cost-benefit analysis of energy-efficient schools.

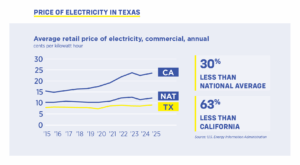

For our case study, we chose a recently completed elementary school in Dallas, Texas — where increasingly severe weather and problems with the electrical grid have upset the status quo of cheap energy and light regulation. As school districts in every state struggle to stretch budgets amid historic political and economic uncertainty, the team looked for opportunities to save money through sustainable design.

Our goal was to understand what it would take to achieve energy independence. We want to be able to have a smart, informed conversation with our clients about up-front costs, return-on-investment and potential savings in annual operational costs.

Starting with a data-rich digital model of the school, the team studied three tiers of additional energy-efficiency investment and their associated costs and energy savings. Tier 1 studied only passive strategies—design elements like demand-control ventilation and increased roof insulation that reduce energy use with little to no added cost. Tier 2 looked at alternative HVAC systems — options for a variable refrigerant flow (VRF) system and heat pumps — to eliminate natural gas. The third-and-final tier provided multiple options for reaching net-zero energy use by adding on-site energy generation infrastructure.

The study shows just how much energy performance can be gained for free, simply with smart, passive design strategies; investing in modern, marginally more expensive HVAC tech; how quickly a net-zero energy school might pay for itself and start producing free energy.

The Results

The results illustrate the significant operational savings available from creating more-energy-efficient buildings. Starting with a passive-only approach, the estimated annual energy cost was $65,000. The optimized HVAC system cut that number by 40% at the up-front cost of $250,000.

The results illustrate the significant operational savings available from creating more-energy-efficient buildings. Starting with a passive-only approach, the estimated annual energy cost was $65,000. The optimized HVAC system cut that number by 40% at the up-front cost of $250,000.

Going a step further, adding PV on the roof would cost an additional $570,000 but would reduce the energy costs to less than $10,000 a year, an 85% savings. To eliminate the electricity bills altogether, the school would need a total cost premium investment of around $1 million. Each of these scenarios would result in a simple payback of 14 to 16 years — potentially much less if energy prices increase, as expected.

The numbers reveal a variety of ways to address energy efficiency, from reevaluating so-called ‘best practices’ to full energy independence. What’s clear is that a high-performing school building is not one-size-fits-all. The point is to give school districts what they need to make informed decisions with their budgets. The return might take 15 years, but over a life span of 50 to100 years, it adds up to a lot of free energy.

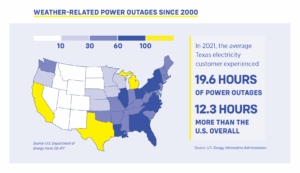

Beyond operational savings, the analysis didn’t include the intangible benefits found in energy-independent facilities. Energy strategies can play an important role in developing more resilient campuses, able to function no matter what happens to the grid. Texas energy and electricity customers experience the third-highest rate of power outages in the country, with almost 20 hours of outages in 2021, according to the most recent US Energy Information Administration data.

More sustainable schools are also, by nature, healthier schools. Campuses with natural daylight, reduced energy demand and no fossil fuel combustion save energy and promote a district’s well-being goals. They also serve as teaching tools, putting engineering and conservation on display on a daily basis.

The data reinforces the importance of including sustainability in the initial planning process, when energy efficiency can be integrated into the design process and tied to the district’s larger goals. In a recent $370 million bond measure, Alamo Heights ISD included funds for “efficiency and sustainability,” earmarking dollars to address more-efficient energy-saving systems.

The data reinforces the importance of including sustainability in the initial planning process, when energy efficiency can be integrated into the design process and tied to the district’s larger goals. In a recent $370 million bond measure, Alamo Heights ISD included funds for “efficiency and sustainability,” earmarking dollars to address more-efficient energy-saving systems.

By taking a tiered approach to the initial analysis, districts can find a comfort level that fits their budget and the priorities of their community. Districts can test the waters, see the savings and incorporate more strategies into future projects.

While on first review, the systems may seem cost prohibitive, the real-world data illustrates an attractive return on investment. Buildings are a one-time expense that, if designed right, create value that can pay off for decades. For cash-poor districts overwhelmed by the maintenance and operation of obsolete, energy-hungry schools, capital improvement dollars provide a unique opportunity to get ahead. The way is clear: prioritizing energy efficiency spending at the right time frees up money later for the education and program expenses that make a real difference for students.

Kate Mraw is the director of K-12 at LPA Design Studios, founder of the firm’s Sustainability & Applied Research team and co-author of “Creating the Regenerative School” (ORO Editions, 2024).

Read more great stories in the July/August edition of School Construction News.